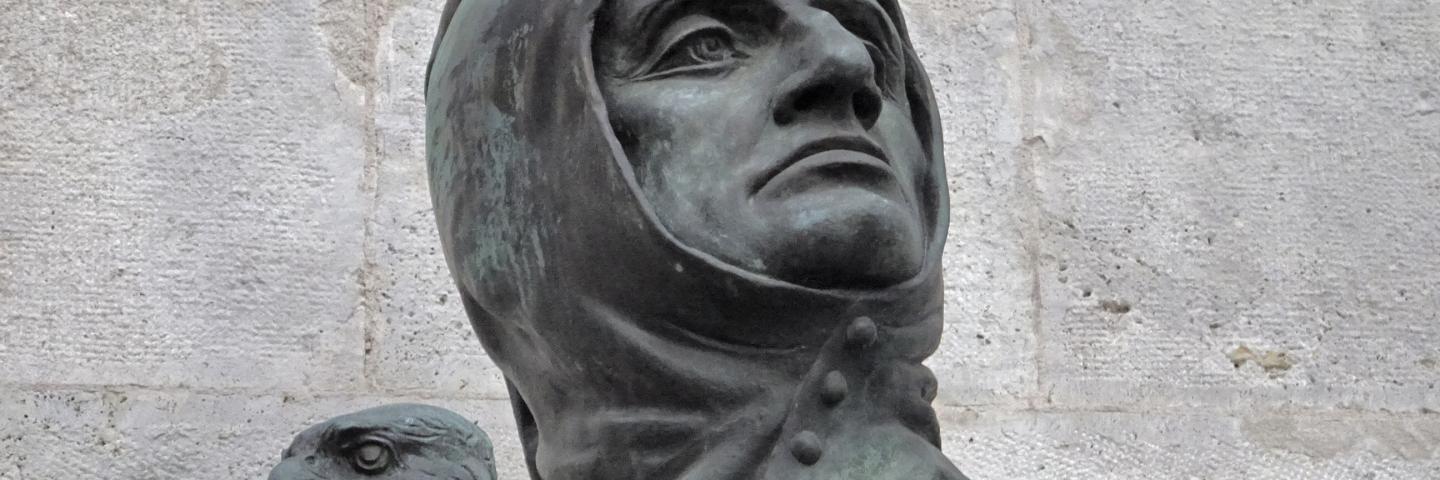

Arne Dekke Eide Næss

Arne Dekke Eide Næss (born in Aker on January 27, 1912; died in Oslo on January 12, 2009) was a Norwegian philosopher, one of the key influences that shaped present day theory of argumentation, but has in his long and very active life also contributed in many ways to a number of other areas. He is best known for his ecological philosophy and his concern for the planet.

Næss studied philosophy with astronomy and mathematics at the University of Oslo and also at the Sorbonne in Paris. In 1933 he took an M.A. at the University of Oslo, being the youngest person ever to take that degree. In 1934 –1935, when he studied in Vienna, he got into touch with the logical empiricists of the Vienna Circle. In 1936 he earned his doctorate at the University of Oslo by a dissertation contributing to an empirical and pragmatic philosophy of science: Erkenntnis und wissenschaftliches Verhalten [Knowledge and Scientific Behavior]. The empirical and pragmatic approach was confirmed in his Truth as Conceived by Those Who Are Not Professional Philosophers (1938). In 1938 –1939 he did psychological postdoctoral research in Berkeley and in 1939 he was offered the chair of philosophy at the University of Oslo. He held the chair until an early retirement in 1970. Næss sympathized with the logical empiricists but also criticized them for a dogmatic strain and a lack of empiricism with respect to their own fundamental tenets.In his Wie fordert man heute die empirische Bewegung? Eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Empirismus von Otto Neurath und Rudolph Carnap [How Can the Empirical Movement Be Promoted Today? A Discussion of the Empiricism of Otto Neurath and Rudolf Carnap], which was written in the years 1937–1939, Næss shows how discussions between logical empiricists and philosophers with opposing views could be improved.

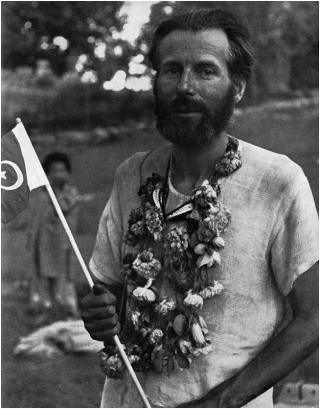

Naess has spent a lifetime in many areas of the philosophic enterprise, from working in the wartime Resistance against the Nazis to defining democracy for UNESCO to systematizing the principles of Gandhian nonviolence as a coherent philosophy. He is most known as the person who coined the term “deep ecology,” an approach to environmental problems that looks for its roots deep in the structure of our western society and the worldviews that guide it. He later preferred the term “ecosophy”, used to distinguish between the philosophy underlying Deep Ecology, and the group practices themselves.

In his “eight-point platform,” formulated together with George Sessions in 1984 while the two were camping in Death Valley, California, Arne Naess offers a convenient overview of deep-ecological principles. It runs as follows:

The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves (synonyms: inherent worth, intrinsic value, inherent value). These values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.

Richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the realization of these values and are also values in themselves.(Updated version: The fundamental interdependence, richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the flourishing of human and non-human life on Earth.) Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs.

Present human interference with the nonhuman world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening.

The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population. The flourishing of nonhuman life requires such a decrease.

Policies must therefore be changed. The changes in policies affect basic economic, technological, and ideological structures. The resulting state of affairs will be deeply different from the present.

The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent worth) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between big and great.

Those who subscribe to the foregoing points have an obligation directly or indirectly to participate in the attempt to implement the necessary changes.

Arne Næss lived and worked at his mountaintop cabin Tvergastein, which was located as far as possible from the social realm, yet close enough to suggest various ways of improving both the household of nature and society. Being situated above everybody else environmentally, socially, and intellectually resulted in a bipolar ecophilosophy in which the good environmental life on the mountaintop and Tvergastein were juxtaposed with the evils down in the valley and urban life in general.