Cornelia Hesse-Honegger

Cornelia Hesse-Honegger (born 1944, Zurich) is a Swiss illustrator, watercolor painter and photographer whose work focuses on the intersection between art and science, zeroing in on the mutagenic effects of radiation on insects. For over two decades she has worked as a scientific illustrator at the Natural History Museum of the University of Zurich, Switzerland. Inspired by the effects witnessed by the tragedy at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and a mutated Drosophila experiment in 1967, she has devoted her life to depicting the effects of radiation and fallout by radioactivity throughout the world. As an accomplished artist and biologist, Cornelia utilizes her scientific background to supplement her skillful artistic ability to create the pieces that you see on this site for your viewing pleasure and displayed in art galleries around the world. Beside her exploits of her own art, Cornelia held a position with the National History Museum at the University of Zurich as a scientific illustrator where her skills became of great use under the tutelage of a zoologist and geneticist Professor Hans Burla. She would hold this position for nearly 25 years. According to Cornelia, she has performed field studies in 25 different locations which she has cataloged 16,367 insects exposed to high radiation levels in Switzerland, United States of America, England, and France.

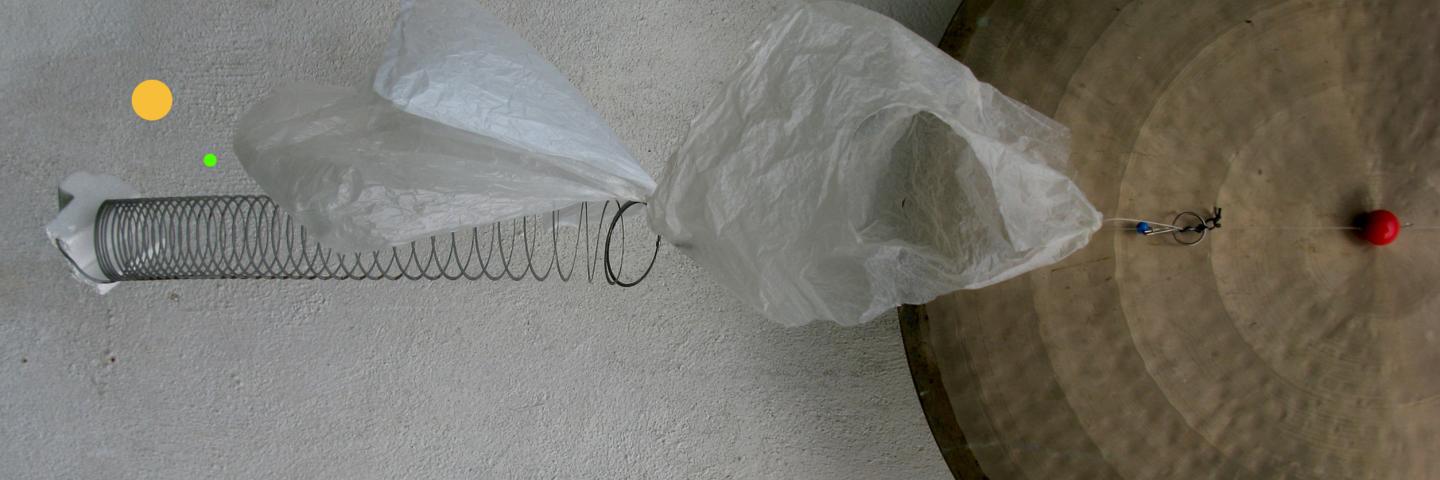

Through this research in the field, as well as through the act of describing these deformities through the pictorial process, I can show that “low-level radiation” emitted from even the best-maintained nuclear plants is in fact extremely dangerous to nature and, thus, also to human beings. In part, what has allowed us to ignore these facts is that we are incapable of seeing the damage. This is, to some degree, a question about the relationship between seeing and knowing. Today, we consider scientific drawings to be mere illustrations, visual representations of what we already know—we think these illustrations show us what has already been seen, thought, and said. But from the Middle Ages until the twentieth century, scientists used illustration as a primary mode of research, as a means of seeing and knowing what cannot be seen or known without the act of connecting eye and hand. I believe in this tradition of using drawing and painting to research nature. My drawings make visible; they are a form of non-verbal communication.

The language of disturbance is the language that we humans have chosen, and it is this language that we leave for our children. Instead of becoming more reasonable about the use of atomic energy, our society now tolerates the worst. My hope is that my work can help open our eyes to what we are doing.