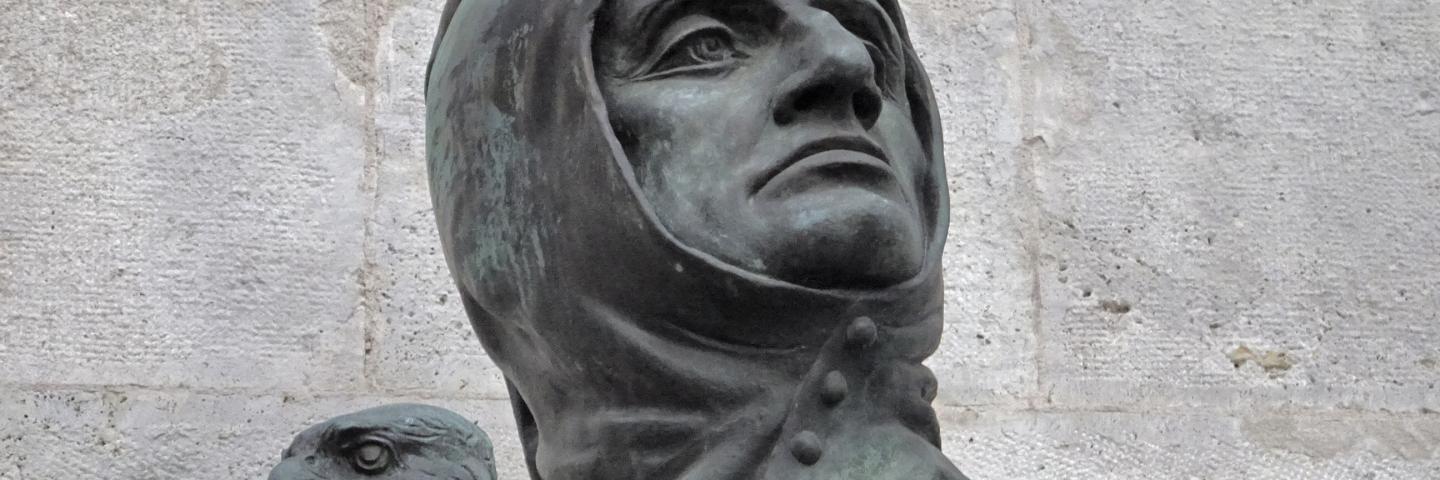

Paul Shepard

Paul Howe Shepard, Jr. (1925 - 1996) was an American environmentalist and author best known for introducing the "Pleistocene paradigm" to deep ecology. He lectured and taught biology at Knox College, Smith College, Dartmouth College, and Claremont College in a career that spanned more than 40 years. From 1973 until his retirement in 1994 he taught at Pitzer College and Claremont Graduate University. His works have attempted to establish a normative framework in terms of evolutionary theory and developmental psychology. He offers a critique of sedentism/civilization and advocates modeling human lifestyles on those of nomadic prehistoric humans. He explored the connections between domestication, language, and cognition. Based on his early study of modern ethnographic literature examining contemporary nature-based peoples, Shepard created a developmental model for understanding the role of sustained contact with nature in healthy human psychological development, positing that humans, having spent 99% of their social history in hunting and gathering environments, are therefore evolutionarilly dependent on nature for proper emotional and psychological growth and development. Drawing from ideas of neoteny, Shepard postulated that many humans in post-agricultural society are often not fully mature, but are trapped in infantilism or an adolescent state.

Shepard became one of the leading voices in what was then a nascent environmental movement in a book that became a standard text for introductory environmental studies classes across the nation: The Subversive Science: Essays Towards an Ecology of Man (1969). The intellectual tenor of that book can be caught in a single sentence: “The ideological status of ecology is that of a resistance movement. That notion essentially nails the status of deep ecology, either in a narrow sense as limited to the ecophilosophical aspects of environmental policy, or in a larger, more Naess-like sense of including peace and social justice issues.

Books

Where We Belong by Paul Shepard, ed. by Florence R. Shepard with an Introduction by Kenneth Helphand (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2003).

Encounters With Nature: Essays by Paul Shepard, ed. by Florence R. Shepard with an Introduction by David Petersen, (Washington, D.C: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 1999).

Coming Home to the Pleistocene, ed. by Florence R. Shepard (Washington D.C. : Island Press/Shearwater Books, 1998).

Nature and Madness, with a Foreword by C.L.Rawlins (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1998) (San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books, 1982).

Thinking Animals: Animals and the Development of Human Intelligence, with a Foreword by Max Oelschlaeger (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1998) (New York: The Viking Press, 1978)

The Tender Carnivore and the Sacred Game with a Foreword by George Sessions (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1998) (NYC, NY: Scribners, 1973).

Traces of an Omnivore, with an Introduction by Jack Turner (Washington, D. C.: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 1996).

The Only World We’ve Got : A Paul Shepard Reader (San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books, 1996).

The Others: How Animals Made Us Human (Washington, D. C.: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 1996).

Man in the Landscape: An Historic View of the Esthetics of Nature (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2002)(College Station, TX: Texas A & M University Press, 1991) (NYC, NY: Knopf, 1967).

The Sacred Paw: The Bear in Nature, Myth, and Literature (with Barry Sanders) (NYC, NY: The Viking Press, 1985) (New York: Arcana Books, Penguin, 1992).

Environ/mental: Essays on the Planet as Home (with Daniel McKinley) (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1971).

The Subversive Science: Essays Toward an Ecology of Man (with Daniel McKinley) (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1969).

MESSAGE FROM A BEAR

In late 1994, Paul Shepard gave a talk, “The Origin of the Metaphor: The Animal Connection,” as part of the “Writings on the Imagination” lecture series at the Museum of Natural History in NYC. (Full text included in The Others, Island Press/Shearwater Books, pages 331-333.) He ended his remarks with “a letter delivered to me by a bear,” addressed to humanity from the Others, the animals. These words were among the last spoken on a public occasion before his death from cancer in 1996.

Dear Primate P. Shepard and Interested Parties:

We nurtured the humans from a time before they were in the present form. When we first drew around them they were, like all animals, secure in a modest niche. Their evident peculiarities were clearly higher primate in their obsession, social status, and personal identity. In that respect they had grown smart, subtle, and devious, committed to a syndrome of tumultuous, aseasonal, erotic, hierarchic power.

Like their nearest kin, they had elevated a certain kind of attention to a remarkable acuity which made them caring, protective, mean, and nasty in the peculiar combination of squinched facial feature and general pettiness of monkeys.

In ancient savannas we slowly teased them out of their chauvinism. In our plumage we gave them aesthetics. In our courtships we tutored them in dance. In the gestures of antlered heads we showed them ceremony and the power of the mask. In our running hooves we revealed the secret of grain. As meat we courted them from within.

As foragers, their glance shifted a little from corms and rootlets, from the incessant bickering and scuffling of their inherited social introversion. They began looking at the horizon, where some of us were both danger and greater substance.

At first it was just a nudge–food stolen from the residue of lion kills, contended for with jackals and vultures, the search for hidden newborn gazelles, slow turtles, and eggs. We gradually became for them objects of thought, of remembering, telling, planning, and puzzling us out as the mystery of energy itself.

We tutored them from the outside. Dancing us, they began to see in us performances of their ideas and feelings. We became the concreteness of their own secret selves. We ate them and were eaten by them and so taught them the first metaphor of their frantic sociality: the outerness of themselves, and ourselves as their inwardness.

As a bequest of protein we broke the incessant round of herbivorous munching, giving them leisure. This made possible the lithe repose of apprentice predation and a new meaning for rumination, freeing them from the drudgery of browsing and the grip of relentless interpersonal strife. Bringing them into omnivorousness, we transformed them forever and they entered the game as a different player.

Not that they abandoned their appetite for greens and fruits, but enlarged it to seeds and meat, and to the risky landscapes of the mind. The savanna or tundra was essential to this tutorial, as a spaciousness open to infinite strategies of pursuit and escape, stretching the senses to their most distant reference. Their thought was invited to a new kind of executorship, incorporating remembrance and planning, to parallels between themselves and the Others and to words-our names-that enabled them to share images and ideas.

Having been committed in this way, first as food and then as the imagery of a great variety of events and processes, from signs in dreams to symbols in metaphysics, we have accompanied humans ever since. Having made them human, we continue to do so individually, and now serve more and more in therapeutic ways, holding their hands, so to speak, as they kill our wildness.

As slaves we stay close. As something to “pet” and to speak to, someone to be there and need them, to be their first lesson in otherness, we have shared their homes for ten thousand years. They have made that tie a bond. From the private home we have gone out to the wounded and lonely, to those yearning for unqualified devotion–to hospitals, hospices, homes for the aged, wards of the sick, the enclaves of the handicapped and retarded, and prison.

All that is well enough, but it involves only our minimal, domesticated selves, not our wild and perfect forms. It smells of dependency.

They still do not realize that they need us, thinking that we are simply one more comfort or curiosity. We have not regained the central place in their thought or meaning at the heart of their ecology and philosophy. Too often we are merely physical reality, mindless passion and brutality, or abstract tropes and symbols.

Sometimes we have to be underhanded. We slip into their dreams, we hide in the language, disguised in allusion, we mask our philosophical role in “nature aesthetics,” we cavort to entertain. We wait in children’s books, in pretty pictures, as burlesques in cartoons, as toys, designs in the very wallpaper, as rudimentary companion or pets.

We are marginalized, trivialized. We have sunk to being objects, commodities, possessions. We remain meat and hides, but only as a due and not as sacred gifts. They have forgotten how to learn the future from us, to follow our example, to heal themselves with our tissues and organs, forgotten that just watching our wild selves can be healing. Once we were the bridges, exemplars of change, mediators with the future and the unseen.

Their own numbers leave little room for us, and in this is their great misunderstanding. They are wrong about our departure, thinking it to be a part of their progress instead of their emptying. When we have gone they will not know who they are.

Supposing themselves to be the purpose of it all, purpose will elude them. Their world will fade into an endless dusk with no whippoorwill to call the owl in the evening and no thrush to make a dawn.

–The Others

source: paulhoweshepard.wordpress.com