Karl David Kryter

Karl David Kryter (Born 1911 in Indianapolis, USA, died 2013) was a world-renowned scientist of Psycho-Acoustics and Audition and Engineering Psychology. Karl received his bachelor's degree from Butler University in Indiana in 1939, and his doctorate from the University of Rochester in New York in 1943. He was a Research Fellow in Harvard University's Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (Founded in 1940 as part of an initiative to reduce noise problems experienced by bomber pilots during the War. The Psycho-Acoustic laboratory specialized in research on the physiological and psychological processes involved in sound perception. It was headed by S.S. Stevens. During the War, the Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory collaborated extensively with another Harvard Institution, the Electro-Acoustic Laboratory headed by Leo Leroy Beranek.

From 1945 to 1948, Karl was a Research and Teaching Fellow at Harvard University. During the war years, he worked for the War Manpower Commission on communications research and development for the Armed Services. From 1948 to 1957, he was Director of the Operational Applications Laboratory at the Air Force Air Research and Development Command in Washington DC. He subsequently worked for Bolt, Beranek and Newman in Massachusetts as Head, Department of Psychoacoustics, and from 1965 until retirement, as Director of the Sensory Sciences Research Center at Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, California. Until his death, Karl maintained a position of Associate Professor at San Diego State University in California. Karl's professional life was dedicated to the advancement of the sciences and their role in the betterment of the human condition. He was an active member of the American Psychological Association, the American Acoustical Society, the Executive Council of the National Academy of Science, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Standards Association and the International Electrotechnical Commission. He worked on numerous modern-day noise issues including aircraft noise and the sonic boom, and acted as a Friend of the Court in cases of noise pollution. He traveled widely to participate in conferences and seminars at The Karolinksa Institute Stockholm Sweden, The University of Auckland New Zealand, Kobe and Doshisha Universities and the Institute of Public Health, Japan, and the Institute of Acoustics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China. His publications include two famous books: "The Effects of Noise on Man" and "Physiological, Psychological, and Social Effect of Noise," and numerous publications in professional journals.

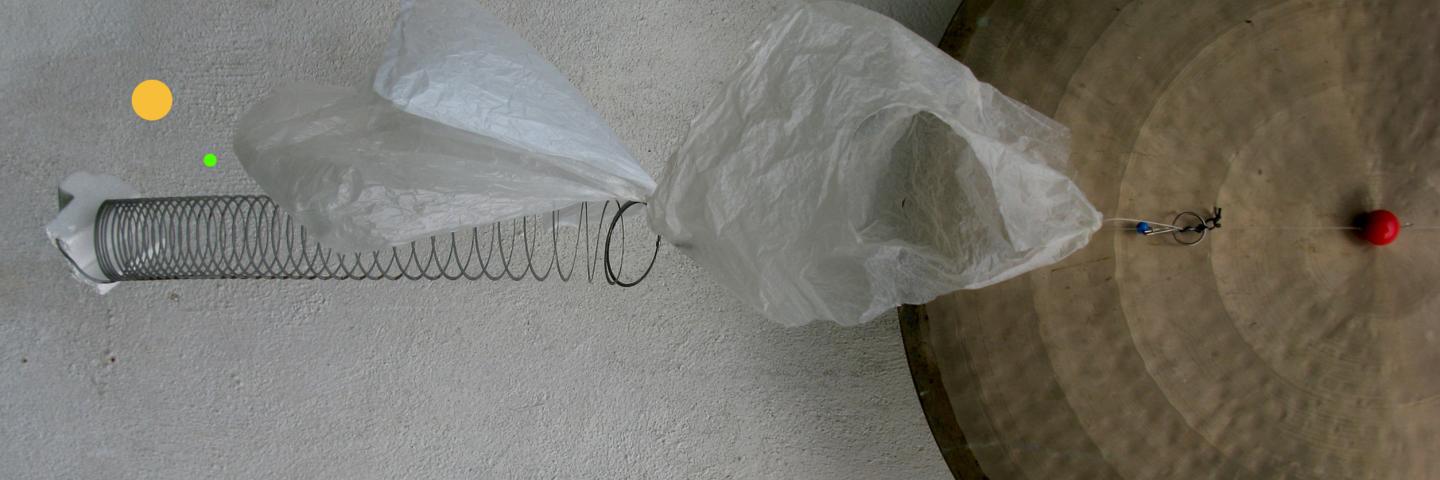

See example here:

PREDICTION OF EFFECTS OF NOISE ON MAN

By Karl D. Kryter

Stanford Research Institute

Published by Academic Press, NY, 1970

The book provides the fundamental definitions of sound, its measurement, and concepts of the basic functioning, and the attributes of the auditory system. The text also presents along with their experimental basis, procedures for estimating from physical measures of noise its effects on man's auditory system and speech communications. The last part of the book is devoted to man's nonauditory system responses and includes information about the effects of noise on work performance, sleep, feelings of pain, vision, and blood circulation.

The major basic deleterious effects of noise on man are masking of speech, damage to hearing, and perceived noisiness or unwantedness. Present knowledge permits accurate quantitative prediction from spectral measures of a noise and the effects of the noise on the understandability of speech and on temporary and permanent deafness. Methods for the quantitative prediction from spectral measures of noise and the basic effects of noise on perceived noisiness and behavior of people have been developed to the point that standarization of these methods is perhaps possible.

In the standardized terminology of acoustics, "noise" is defined as unwanted sound. However, confusion sometimes results in the use of the word noise as an appellation for unwanted sound because there are two general classes of "unwantedness." In the first category the sound signifies or carries information about the sound's source which the listener has learned to associate with some unpleasantness not due to the physical sound but due to some other attribute of the source. For instance, the sound of the fingernail on the blackboard suggests perhaps an unpleasant feeling in tissues under the fingernail; the sound of an airplane suggests, to some persons, fear that the plane may be falling on their home; a baby's cry causes anguish in a mother; the squeak of a floorboard is frightening because it may indicate the presence of a prowler. In all these examples, it is not the sound as noise that is unwanted (although for other reasons it may also be unwanted), but the information it conveys to the listener. This information is strongly influenced by past experiences of each individual and, in the author's opinion, its effects cannot be quantitatively related to the physical characteristics of the sounds.

In the second category, the unwanted effects of sounds are related to physical characteristics of the sound in ways that are more or less universal and invariant for all people, These effects are both physiological and psychological; the effects are psychological only in the sense that man learns through normal experience of the relations between the characteristics of sounds and their basic perceptual effects. The effects referred to and to be discussed subsequently are the masking of wanted sounds, particularly speech, auditory fatigue, loudness or perhaps some general quality of bothersomeness or distractiveness, and possibly startle (although, because of man's ability to adapt to repeated stimulations, this effect will vary in time). These effects presumably are very similar for all people, not dependent on learning nor can they for the most part be "unlearned," and quantitatively related to the physical nature of sounds. Because of these characteristics, they deserve the attention of persons interested or involved in the design of devices that generate sound, in the control of the sound during its transmission, or in the protection of the health and well-being of people exposed to the sound. Indeed, nearly all measurement of sound by acoustical engineers is made for the immediate or ultimate purpose of evaluating the effects of the sound on man. ....

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Perhaps the most beneficial and practical applications of effective perceived noise level, and when possible Composite Noise Rating, are not with respect to present-day noises or noise environments but (1) as guides for the design and operation of so-called quiet engines, in the forecasting of noise environments for neighborhoods and communities as new airports, roadways, and industries are developed and used, and as guides for setting acoustical standards for new housing.