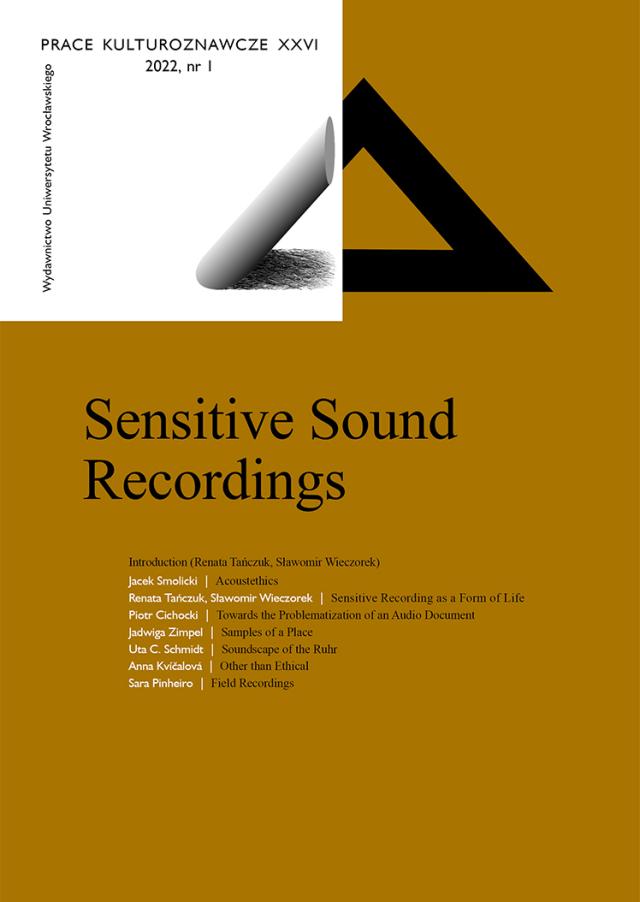

The Second Life of Recorded Sounds, 2020 publication

We are happy to announce that the publication “Sensitive Sound Recordings” after our online meeting in Wroclaw from 2020 was just published (now on-line, very soon on-paper).

“We define sensitive sound recordings as ones linked to the experiences of trauma, exclusion, and injustice of those whose voices were recorded, as well as the communities to which they belonged. They are correlates of the ‘sensitive heritage’ and sometimes the ‘difficult heritage’ of communities. Broadening the scope of the term ‘sensitive recordings’ in relation to the above-mentioned definition, we could also include recordings that violate taboos, for example, some cultural contexts, recordings of religious ceremonies “or intimate situations”.

“Click, browse, like, share, save, listen!”

Renata Tańczuk, Sławomir Wieczorek

Authors and Editors

Introduction

In 2020, the Soundscape Research Studio, the Institute of Cultural Studies, the Institute of Musicology at the University of Wrocław, and the Central European Network for Sonic Ecologies organized the international academic conference The Second Life Of Recorded Sounds online conferencedevoted to the reuse of archival, non-musical recordings in academic research, artistic practices, as well as in ecological and political activism, and education. The use of sound recordings for purposes other than those for which they were originally recorded raises questions about their identity, instrumentalization, and the transformations they undergo in new cultural, social, and political contexts. There is a need for critical reflection on the recording process itself, which can be seen as a form of appropriating the heritage of colonized and marginalized communities, and on sound technologies as instruments for perpetuating and reproducing colonial power and racism.

The conference papers dealt, among other things, with ethical issues related to sound recording, listening to recordings, and re-mediation. Research focused on biographies of problematic sound legacies, for example wiretaps or recordings made in colonial contexts and in prisoner-of-war camps during World War I. Presentations on ethical issues related to the collection and use of recordings, for example in the context of bio- and necropolitics, as well as the decolonization of sound archives and the politics of collecting, inspired us to reflect on “sensitive sound recordings.” By defining the object of our interest in this way, we also invoke the notion of “sensitive heritage,” which appears in discussions on museum collections of artifacts from outside Western culture and their restitution.

In our article presented in this issue of “Prace Kulturoznawcze”, we define “sensitive sound recordings” as ones linked to the experiences of trauma, exclusion, and injustice of those whose voices were recorded, as well as the communities to which they belonged. They are correlates of the “sensitive heritage” and sometimes the “difficult heritage” (S. Macdonald) of communities. Broadening the scope of the term “sensitive recordings” in relation to the above-mentioned definition, we could also include recordings that violate taboos, for example, in some cultural contexts, recordings of religious ceremonies or intimate situations.

Such recordings, sometimes because of the manner and context of their creation, confront the listener and user with a whole spectrum of complex problems related to the right to collect, dispose, and listen to them, as well as the social, political and ethical consequences of their reuse in research, educational, and artistic practices. Approaching the recording as a form of life and analyzing its biography allows us to grasp its social causality and transformation.

“Sensitive sound recordings” refer to “difficult” and “moving” recordings that evoke affects and emotions. They constitute a kind of “sensitive heritage” of communities, and sometimes also a problematic heritage, such as recordings of wiretaps. “Sensitive recordings” do not allow listeners to be indifferent; they demand from their users, who include researchers, a responsible, caring attitude.

The concept of acoustethics proposed by Jacek Smolicki, which emphasizes the need for a reflexive approach to sound recording (a complex process that always takes place in an area understood as a space of diverse and non-obvious relations between acting and interacting actors — human subjects, technology, places, etc.), takes into account the specificity of sensitive recordings.

Sensitive sound recordings not only evoke afective and emotional responses, but are also capable of conveying the affective dimension of particular places and entering into a complex and dynamic relationship with meta-comments about themselves. This causality of recordings is captured in an interesting way by Jadwiga Zimpel, amu.academia.edu who wonders about their status as an element of the cultural heritage of cities. The problem of transforming a recording into a cultural heritage correlate is, in turn, taken up by Uta C. Schmidt, a co-founder of the Ruhr Sound Landscape Archive.

Recording, storing, listening to, and using sound recordings are cultural practices of great political significance. In times of modern surveillance techniques, wars, and migration, the political entanglement of recordings and sonic big data becomes an issue that should be carefully examined. In this volume it is raised by Sara Pinheiro by posing a series of questions not only about the political nature of sound, but also about the political agency of field recording.

A different perspective on the approach to sensitive recordings is outlined by Anna Kvíčalová. The author focuses on the production processes of new knowledge about sound and formation of new listening techniques that take place in fonoscopy laboratories during the analysis of recordings from security service wiretaps.

Conference Participants

Dariusz Brzostek (Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń)

Anna Maria Busse Berger (University of California, Davis)

Piotr Cichocki (University of Warsaw)

Anna Markowska (University of Wrocław)

Uta Schmidt, Richard Ortmann (University of Duisburg-Essen)

Michał Witek (University of Wrocław)

Jadwiga Zimpel (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań)

Antoni Michnik (The Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw)

Jacek Smolicki (Linköping University)

Jarosław Jaworek (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań)

Anna Kvíčalová (Charles University, Prague)

Csaba Hajnoczy (Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, Budapest)

Paweł Szroniak (Wrocław Contemporary Museum)

Beata Anna Targosz (Berlin)

Michal Kindernay (Prague)

Pedro Oliveira (Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, 2021)

Magdalena Zdrodowska (Jagiellonian University, Cracow)

Hans Ulrich Wagner (Leibniz-Institute for Media Research, Hans-Bredow-Institute, Hamburg)

Sara Pinheiro (CAS/FAMU Prague; University of Bangor)

Renata Tańczuk (University of Wrocław)

Sławomir Wieczorek (University of Wrocław)

Jan Krtička (Jan Evangelista Purkyně University, Ústí nad Labem)

Julius Fujak (Constantine the Philosopher University, Nitra)

Daniel Brožek (sound art curator, Wrocław)

OR poiesis (alias Petra Kapš) (Maribor)

Gerard Lebik (Sanatorium of Sound, Sokołowsko)

Online publication: https://wuwr.pl/pkult/issue

Conference: The-Second-Life-Of-Recorded-Sounds-online-conference